You’re Done!

In the first few days of 2026, massive headlines have been coming fast and furious:

The U.S. captures Maduro

Massive fraud uncovered in Minnesota involving Somali nationals, government officials, congressional leaders, the governor, and local politicians

Death Toll Surpasses 2,500 in Iran Protests

U.S. officials meet with Denmark over a potential deal involving Greenland

And we’re barely a week in.

These are all enormous stories, but the one with the most direct and immediate economic implications may be this: Trump says U.S. to ban large investors from buying homes (CNBC).

2025 delivered no shortage of wild headlines as Trump took office and launched DOGE, but many of those stories focused on waste that felt abstract to everyday Americans. Housing is different. This issue is tangible, emotional, and foundational to the American Dream. We should note that anything Trump proposes is reflexively protested by the left, regardless of merit, so this idea is far from guaranteed to be codified by Congress. Still, the underlying concern is real: if current trends continue, middle-class Americans—especially younger families—have little chance of achieving what their parents did.

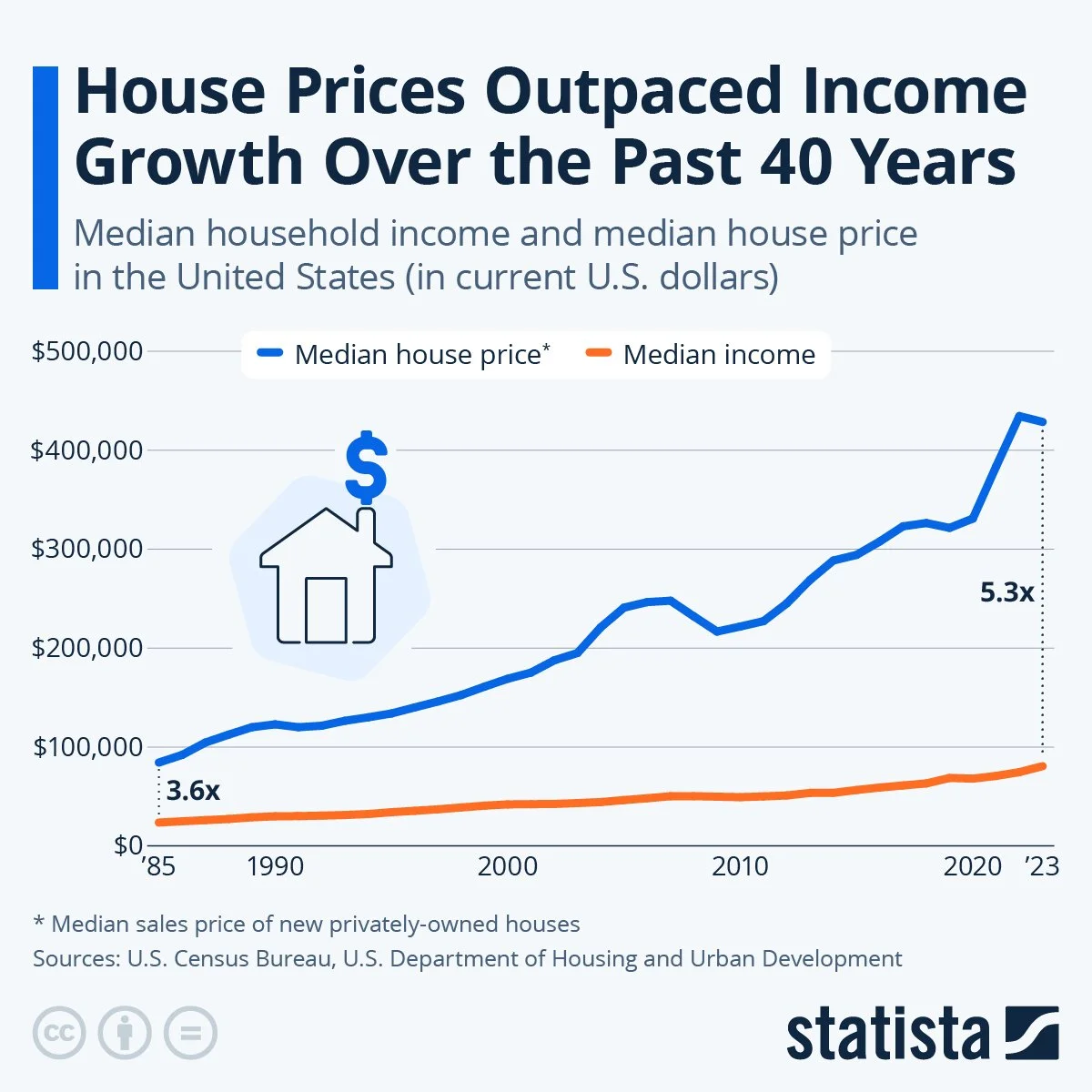

The data is imperfect, but a quick survey suggests that roughly 2–4% of U.S. single-family homes are currently owned by large investors (read: private equity). On its face, that figure doesn’t sound alarming. The trend, however, tells a very different story

Home prices have been outpacing wages for roughly 40 years, but two periods deserve special attention: the 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis and the COVID era. Private-equity firms played a crucial role in setting the floor during the housing collapse, stepping in with cheap capital and a favorable regulatory backdrop to buy when few others would. That served an important purpose at the time. But as is often the case, something that began with reasonable intentions has produced unintended consequences.

When housing briefly dipped in 2020, investors rushed in for another bite at the apple. What followed was the fastest acceleration in home prices on record. Asset owners benefited enormously, but the environment became increasingly hostile for anyone seeking upward mobility—most notably young Americans. This problem has been compounded by the lingering trauma of 2008, which left many investors wary of deploying large amounts of capital into homebuilders or banks. As a result, housing supply remains structurally constrained. Despite encouragement from figures like President Trump and Warren Buffett, new construction simply hasn’t kept pace. Increasing supply can’t move the needle fast enough for families trying to buy affordable single-family homes today.

In response, the Trump Administration has floated several policy ideas: pressuring the Fed to lower rates, ordering Fannie and Freddie to purchase mortgage bonds, and even proposing 50-year mortgages. We view none of these as particularly healthy solutions for consumers or the broader economy.

So how does 2–4% ownership translate into real affordability pressure? Because homes change hands slowly. Estimates suggest that in 2024 and 2025, between 27% and 33% of home purchases went to investors rather than owner-occupants, up sharply from an average of 18.5% between 2020 and 2023. That begins to look like serious crowding-out in a market that represents the primary store of wealth for most American families. Removing nearly a third of buyers could meaningfully change the dynamics.

Banning or materially restricting private-equity investment in single-family homes would not be without consequences. First, it would likely reduce liquidity in housing markets during downturns, making price declines sharper and recoveries slower when traditional buyers step back. Second, capital would be forced into other asset classes, potentially inflating valuations in multifamily housing, commercial real estate, or public securities. Third, reduced investor participation could slow renovation and redevelopment activity in marginal housing stock, particularly in lower-income areas where institutional capital often funds repairs that individual buyers cannot. These tradeoffs matter, even if the policy goal—improving affordability—is well intentioned.

So, what does this all mean for investors and the economy? For private-equity firms, the most immediate outcome would be reallocation of capital. Multifamily housing remains an attractive option for those who value the tangible nature of real assets, and other segments of real estate could also see incremental inflows. One man gathers what another man spills. Some displaced capital may ultimately find its way into operating businesses or public markets instead. For consumers (particularly young families), the effects will hinge on whether reduced investor participation meaningfully improves access and pricing, or whether broader supply constraints continue to dominate outcomes. As with most policy shifts, the ultimate impact will depend less on intent and more on how markets adapt over time.